Childbirth Should Not Be a Battlefield

A conversation with Allison Yarrow, author of "Birth Control: The Insidious Power of Men Over Motherhood"

Matriarchy Report is a reader-supported publication. To support independent feminist journalism, become a paid subscriber, starting at $5 a month, using the link below.

If this newsletter is meaningful to you, your help (likes, comments, shares, subscriptions) make a big difference in making this newsletter sustainable.

I was 42 when I had my daughter; my only pregnancy and my only child. I’m in a hetero marriage and we got pregnant after nine months, without interventions. The pregnancy itself was a joy, really – no fibroids, no gestational diabetes, no debilitating migraines – just bagels and tomatoes, and a lot of time to myself that I just didn’t appreciate hardly enough.

I never considered a home birth – too scared at my age of possible complications –and when we went to the hospital for a check up nine days after the estimated due date, I was told that her heart rate was dropping.

After that, things went quickly: I was induced with pitocin and was in active labor four hours later.

My daughter was born vaginally, with no complications. The anesthesiologist made a snide remark when I declined an epidural, but I made it through labor without one, which felt significant at the time, although now I feel mixed about the kind of outsized pride I took in that decision.

I share all this because I came to Allison Yarrow’s newest book, Birth Control: The Insidious Power of Men Over Motherhood, with some fear. I’m always on alert for other people’s judgment about my birth experience: that there were ways it could have been more natural, or safer, or somehow just more…transcendent.

It’s one of the many ways that women and birthing people get caught in the ideas, expectations, and external pressures around pregnancy and birth – and it foreshadows the experience of contemporary motherhood: that no matter how hard you work, or what your circumstances are, you’re never doing it right.

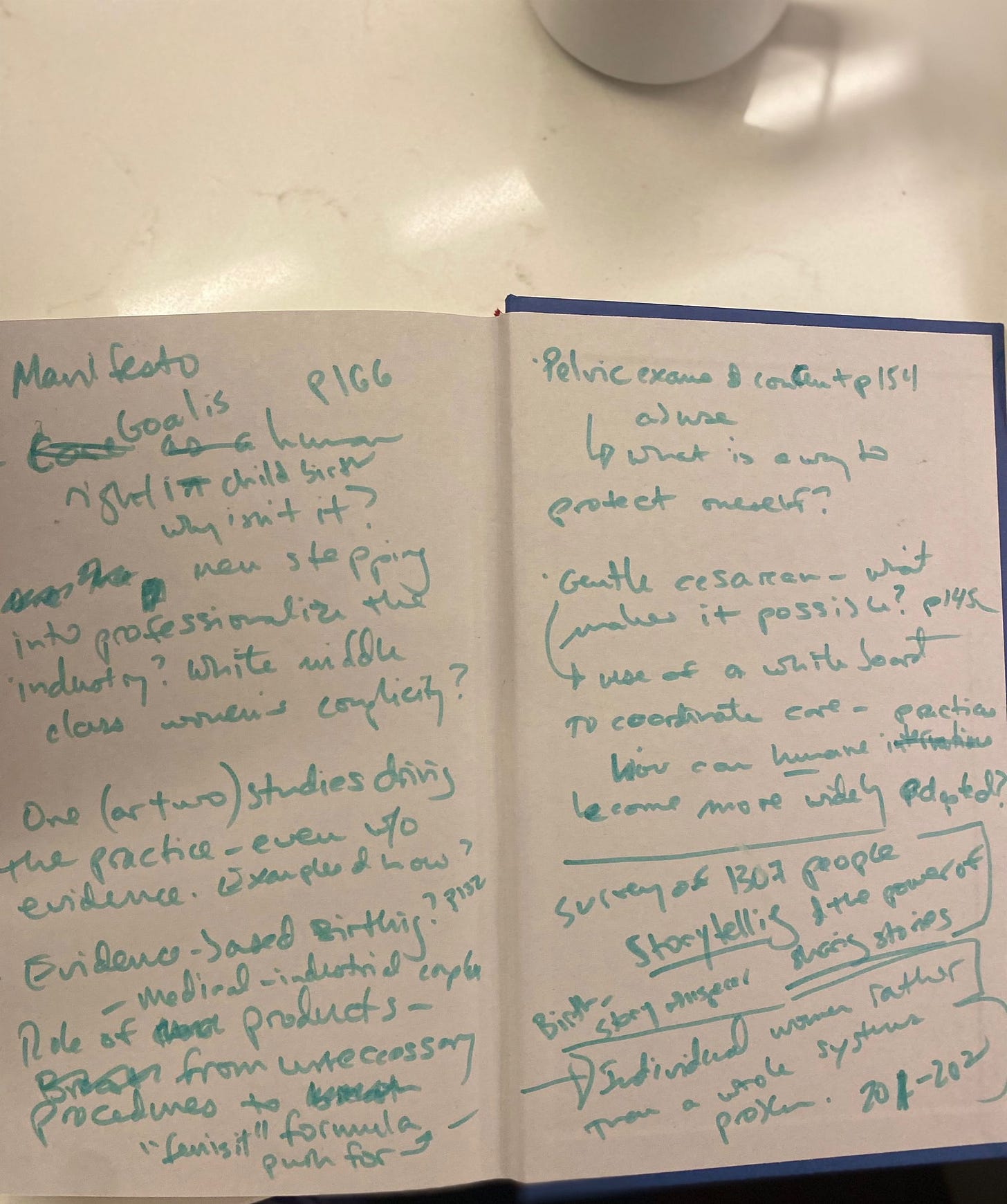

So I was relieved – really, truly relieved – when I opened her book and couldn’t stop reading it. I scribbled all over it, and immediately wanted to talk to her.

Yarrow is obsessed with birth stories.

“I have no boundaries with this stuff,” she told me when we spole. “I'm just constantly asking people about their birth stories, and sharing my own.”

Birth Control weaves together hundreds of stories: stories she heard talking to people on the sidewalk, stories gathered through a formal survey of over thirteen hundred people, stories from doulas, midwives, nurses, OB’s, and researchers.

And to be blunt, it’s a damning book: it describes a system of coercion and abuse, in which birthing people are given few choices over their own experience of pregnancy and birth.

But it’s also a hopeful book, because we have so much information about what works better to support people – all people – in their birthing experiences.

It started with her own experience. Yarrow is a feminist journalist – her first book is 90s Bitch: Media, Culture and the Failed Promise of Gender Equality, and she’d been writing about the intersection of racism and sexism for years.

So when she started taking childbirth education classes during her first pregnancy, Yarrow got nervous – and curious. A lot of the things she was learning about focused on how to protect yourself in the hospital.

“Why are we learning about playing defense with the people who are supposed to be taking care of our bodies?” she wondered.

Yarrow and I talked back in July, before Birth Control had been released – it’s since been reviewed and talked about everywhere from the New York Times to Elle to my local public radio station – and we discussed everything from to the overuse of fetal heart monitors to the possibility of more gentle c-sections to how to respond when coercion is disguised as caregiving.

I edited our conversation for length and clarity.

This book is packed with data and interviews, and it reads like a manifesto. The goal you’re seeking is “human rights in childbirth – every birthing person at the center of their care and experience.”

This, you say, would be “complete shift in who has the power in childbirth.”

So, my question is – why isn’t it this way already?

If you asked most people, they wouldn't say that human rights are denied to people in childbirth. But what I've come to see through the evidence is: We are coerced. We are abused at a time when we are incredibly vulnerable.

We put our trust in people who are dedicating their lives to being healthcare heroes, who go into this field because they want to take care of people, and they want to be part of life coming into the world.

But this is happening in a system that is intended to take our rights away from us, because that is more profitable.

More than 90% of births occur in the hospital, and you may have a great relationship with your provider, but the goals of that system are to move you through that place as quickly as possible.

And so every intervention is offered, or coerced, or forced upon people to move them through an assembly line. Because the rooms that they're in are incredibly profitable rooms, and moving people through is what creates profit.

Most people can give birth without intervention. When intervention is needed, we definitely know how to do that in the hospital. We have the best technology, certainly in this country, but it's being overused and applied to every birth.

And in that model, human rights are being taken away.

The subtitle of the book is “The Insidious Power of Men over Motherhood.” How did the intervention of men into this process become so dangerous for birthing people?

Historically, as the country was being created, there wasn't medical school. There weren't nursing degrees. Midwives apprenticed and attended thousands of births over their careers. And that model worked very well and was largely very safe, based on what we know from the data.

When medical schools were established in this country, doctors realized that if they wanted to have business, they needed to attend childbirth, because childbirth was happening all over the place and all the time. So they apprenticed with midwives and they learned their techniques. They were white men, and they said: “We have tools, and we have drugs, we have technologies, we have expertise, and you will be safer. You will be safer in our hands, and you will be safer in our hospitals.”

And that was a path to regulate midwives out of existence, which is something we're still recovering from today.

If every one of the four million people giving birth in this country wanted to be attended by a midwife, that would be impossible. There aren't enough of them.

I was really – kind of naively – shocked to learn that so little of what happens through pregnancy and childbirth is, in fact, evidence-based.

I've spent years on this and I still cannot believe it.

It is incredibly important that we are using the best data that we have to inform our decision-making. It's not everything – I believe that someone who is giving birth has the right to say what they want and what they do not want

But we want to make sure that the care people are getting is based on the latest evidence. And that's just not the case.

If it were the case, we would not see routine electronic fetal monitoring, for example. This was a technology that was introduced in the mid-century. It was put into hospitals by marketers. It became a tool that doctors were incredibly addicted to – to be able to watch the labor from another room. You don't even have to be in the same room as the person that you're taking care of. You can watch their labor, along with many other laborers from an entirely different location.

What we know about this technology is that there's virtually no evidence to support its use. In fact, it causes intervention. It causes c-sections. According to the Listening to Mothers survey, between 80 and 90 percent of births are still using this technology. It's not an evidence-based technology.

That's an example of not using the best evidence, and there being negative outcomes related to that.

There are a number of examples in the book where you describe how the smallest amount of data or some particular idea takes hold, and ends up driving a whole set of practices in childbirth, practices that actually don't have that much evidence for their effectiveness. One example is this idea of the so-called “obstetrical dilemma.”

Right. So, that is the idea that a bunch of white, male anthropologists posed by looking at bones – not tissues or hormones or any other thing about the body – but just bones, that the female pelvis was inadequate for birth.

With that came the idea that it was actually required that men step in with their tools to aid birth. Because the female pelvis really couldn't do it on its own. That’s how we got to forceps, and vacuum extraction, and other tools, and episiotomies and Cesarean sections.

And just to be clear, you really can't predict a baby's size with a whole lot of accuracy during most of pregnancy. An ultrasound can tell you between weeks about 11 and 14 with the most accuracy the size of a fetus. By the time you get to the end of a pregnancy, there's no good evidence that we can tell the size of a baby.

And yet, there are obstetricians every day telling people, “We really want to just schedule that c-section, because you're carrying a baby that is too big, and we believe that you might not be able to give birth to the baby that you created, based on what we believe.”

That originates from this idea of the obstetric dilemma.

Many of the people you interviewed for this book described harrowing experiences of traumatic exams. You also describe the overuse of pelvic exams – 52 million pelvic exams were performed in the U.S. in 2015 – which, you write, are largely performed out of habit, not necessity. A midwife you interviewed describes contemporary pelvic exams as “assault disguised as care.”

What can we do to protect ourselves from coercion?

First, I want to say that the onus should not be on pregnant and birthing people to prevent assault or to prevent themselves from being coerced or consented to care that they don't want.

But in a system where this is common, things that you can do include, one: declining pelvic exams. You don't have to do pelvic exams. They're overdone. There's not a lot of evidence to support their use in terms of later pregnancy.

They can introduce bacteria, they give providers an opportunity to strip your membranes, which is a procedure that can start labor.

So just say no to the pelvic exam.

Even if they walk in the room and they say, “Okay, it's time for your exam,” you can say, “No, thank you.”

You write, “Forced examination or refusal to stop when asked – aka assault – sounds like this:

“You’re doing great”

“Just another second.”

“You will thank me later.”

“I just need to check.”

“Almost finished.”

Right. I think another thing is really asking providers the right questions before you enter into a care relationship with them, and making sure that you are with providers that understand and practice informed consent. I would ask about c-section rates, and episiotomy rates, so you can know: Am I at a place with a high rate with one of these procedures?

It's really important to know these numbers and to have really frank conversations with providers around these topics, and to make sure that they're comfortable answering your questions, and not threatened by them.

I want to talk about the gentle cesarean and the whiteboard, which you describe in the book as two forms of a more humane practice in childbirth.

The whiteboard strategy is very low-tech technology that different hospitals that decided to center the birthers in their own care experience.

These were all hospitals that had incredibly high C-section rates, and insurers had come to them and said, “We can't pay for this.” So that was actually a big driver of this.

So they took a whiteboard, and on the board goes the name of the person giving birth and everyone caring for that person during their labor, and the status of the labor. The idea is really simple. It's just making sure that everyone on the care team understands what is going on. There's no game of telephone happening where a doctor is talking to a nurse, and they have one understanding of where labor is. And a woman laboring shouldn't really have to be directing the experience as well.

The board really improved outcomes. Everyone in the surveys at one hospital who experienced the board really had wonderful things to say about it. They felt great, cared for, and centered.

The gentle C-section is really this amazing way to give people a birth in which they can feel centered and empowered.

It was just incredible the first time I heard about what it was. This one woman was able to work with her OB, and she had a clear drape instead of an opaque one. So she was able to see her baby lifted up out of her.

Her provider told her to tie her gown in a certain way, so she could just pull one string and it would come down, and she would be able to breastfeed the baby immediately. She was given the baby immediately so they could have skin-to-skin. She felt so cared for and empowered.

Everyone should have the option of a gentle C-section, if they wish, so they can have as many of the women-centered elements of a physiologic birth as possible.

Also, if you're going to have a C-section, you can visit the operating theater beforehand. You can know your surgeon, you can see the place where it's going to happen. These are just simple, obvious, humane things to do, but yet we're not in the habit of doing this.

So last question: Who do you hope will read this book?

Listen, I'd love for everyone to read it. We're all born, we're all connected to it. We're all either going to give birth or we love someone who has, or will.

But specifically, I'm looking at three groups of people who need to read this.

People who are pregnant, and who are thinking about becoming pregnant. They need this information. They need to be able to protect themselves, and they need the stories and the validation.

Also, people who have already given birth. Perhaps it didn't go quite as they expected. They deserve validation, whether they experienced trauma or were coerced into care or just had a different experience.

Lastly, I want providers to read this book. People who go into healthcare – they're heroic. They want to touch lives and change lives. And they need more support to do that than they're getting right now.

I hope this book really uplifts the midwives’ model of care and doula support.

But in hospital environments where the structural culture is so entrenched, and the best evidence isn't always being applied, and where we know that systemic racism and sexism are shaping the care, it's all the more important that they can look at something deeply reported and understand: This is what the people you're caring for are saying about their experiences.

It's important that you understand where things are going right, and where things are going wrong – and what can be improved.

MATRIARCHY REPORT is written by Lane Anderson and Allison Lichter.

Lane Anderson is a writer, journalist, and Clinical Associate Professor at NYU who has won several awards for her writing on inequality and family social issues. She has an MFA from Columbia University. She was raised in Utah and is based in New York City with her partner and young daughter.

Allison Lichter is the Associate Dean at the Newmark School of Journalism at the City University of New York. She has been a writer, producer and editor for radio and print, covering the arts, politics, and the workplace. She was born and raised in Queens, and lives in Brooklyn with her partner and daughter.

Matriarchy Report is a reader-supported publication. To support independent feminist journalism, become a paid subscriber, starting at $5 a month, using the link below.

If this newsletter is meaningful to you, your help (likes, comments, shares, subscriptions) make a big difference in making this newsletter sustainable.

We would love your feedback on Matriarchy Report! Tell us what you think in this short survey. (Bonus: Your participation in the survey instantly enters you in our raffle where you can win a $50 gift card to Bookshop.org!)

Ahhh a friend just messaged me about this post and how it’s bringing up distress from our own gyn birthing experiences. I’m thinking about consent and the passive-aggressive responses doctors give--the ones you and Allison list gave me chills. I’m thinking about the time 7 residents (all men) came into my room unannounced when I was in the stirrups and when I ordered them out I could feel the eye roll and quiet accusations that I was being a bitch.

I’m also thinking about the maternal mortality rate, esp for women of color, in this country.

Illuminating