Mother's Day, Palestinian Liberation, and ritual

A Jewish mother contemplates "Fighting for justice for all of us, not just us."

Hello Subscribers, on Mother's Day we wanted to say a special thank you and hello from MR and thank you for supporting our work, so much of which is about "mothering."

I think of mothering, at its best, as sustaining and honoring life. This is, I think, largely why Mother's Day can be both wonderful and painful. And maddening at times.

I didn't feel like reading much about Mother's Day this year given the painful disregard for life that we are living through right now, but this piece from Allison turned out to be exactly what I need.

So many of our hearts hurt because we want all mothers to be safe, and all children to be safe. Allison offers some beautiful reflections on mothering and liberation here. The piece is linked and excerpted below. I hope that you find it as meaningful and heartening as I do.

Here is a link to an org that I’ve donated to that supports Palestinian mothers and children (if you know of other good ones please feel free to share).

And remember, on Mother’s Day and every day: There's no right way to be a mother. There's no right way to be a woman.

Thank you for being on this journey with us!

"The moral clarity and courage of young people is astounding.”

Last year, I purchased a thin little book with a glorious yellow cover and the tantalizing title, Questions to Ask Before Your Bat Mitzvah. Much like Mother’s Day, there’s a certain predictability to this particular ritual: it’s about a party, sure, and a general concept of tradition and the passing along of …

by Allison Lichter

Last year, I purchased a thin little book with a glorious yellow cover and the tantalizing title, Questions to Ask Before Your Bat Mitzvah.

Much like Mother’s Day, there’s a certain predictability to this particular ritual: it’s about a party, sure, and a general concept of tradition and the passing along of identity.

Like Mother’s Day, the ritual can be hollow and consumerist, or rich and empowering.

I did not have a Bat mitzvah and my 8-year-old child may or may not have one, but I was intrigued by the idea that kids (and grownups) might have a lot of questions to ask about why they would participate in this ritual at all.

I’ve been trying to reimagine Mother’s Day for myself this year, and how I want to participate in it. I want to draw on a history of radical mothers who, in the words of Questions to Ask contributor Esther Farmer, are "fighting for justice, not just us.”

And, also, because what is happening Gaza is horrifying, and because I am Jewish mother to a Jewish child, I also wanted to look into a tradition that has something new to offer around this Jewish ritual, especially as it relates to Palestine.

“Questions to Ask” came out last year, but the questions it’s asking are ones that many people – Jews and non-Jews – are wondering about right now.

It’s a collection of 36 essays that explore questions like “Who cares about bat mitzvahs in such a messed up world?" and “Is it antisemitic to be anti-Zionist?” “How do we really honor the legacy of the Holocaust?” and “What do Palestinian kids do when they turn 13?”

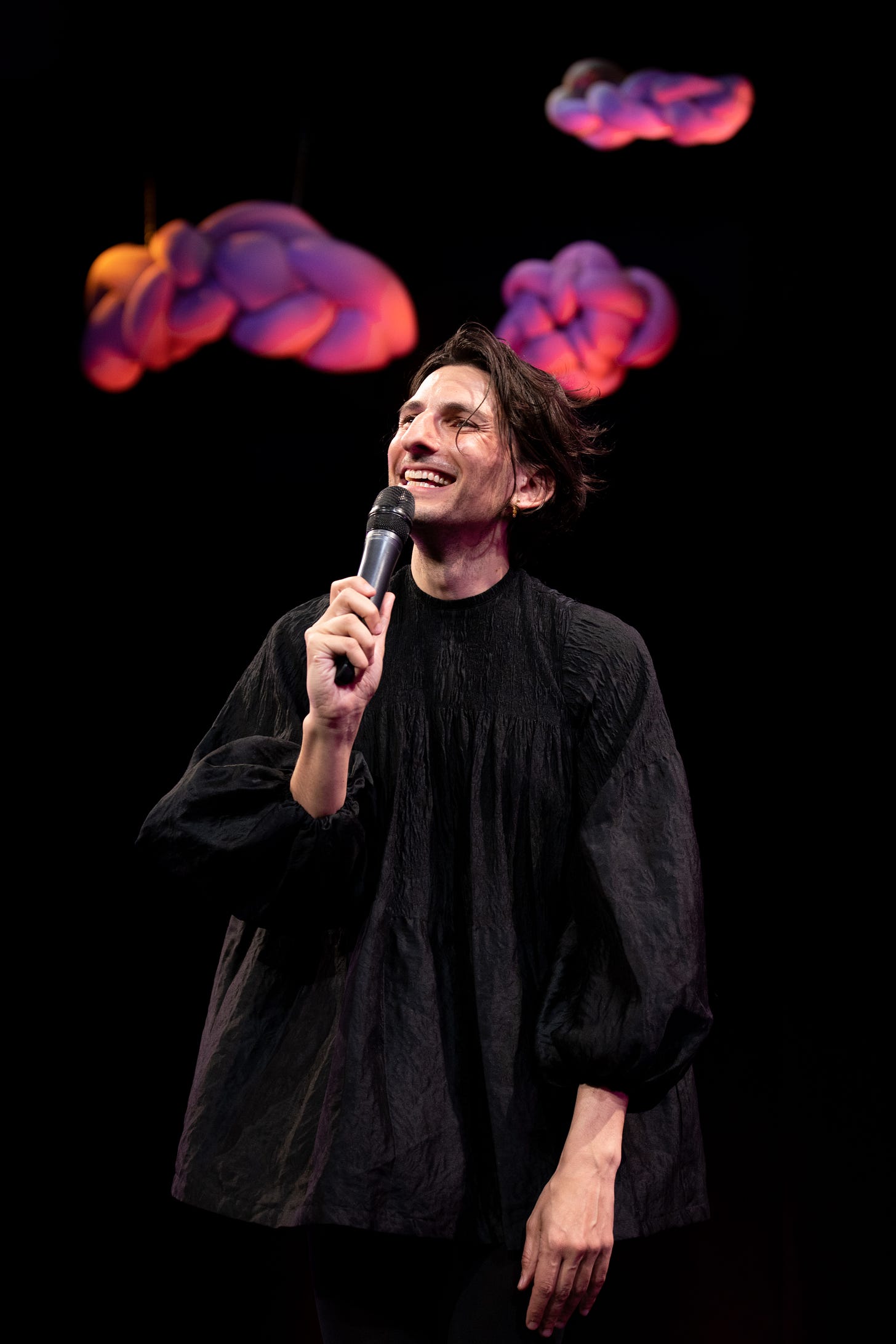

I spoke with one of the book’s editors, Morgan Bassichis, a writer, musician, and activist. The book, they told me, came from a desire for “everyone to have access to radical teachers.”

They’ve explored the B-mitzvah (the gender neutral term) as a topic in their performance work. They use music and humor, they told me, “to explore legacies of Jewish anti-Zionism and radical Jewish history, so many of which have been led and stewarded by queer and feminist and lesbian Jews.”

We spoke recently about Questions to Ask, reinventing ritual, and learning a new Jewish relationship to Palestine. I’ve edited our conversation for clarity and length.

One of your contributors, Dori Midnight, writes that “rituals are full of liberatory potential.” Why did you want to show young people a new way to revisit this particular ritual? What's liberating about that?

The moral clarity and courage of young people is astounding. I've seen so many young people use their B-mitzvahs to explore different issues that matter to them. For so many of us who are adults and who did this ritual when we were 13, it was somewhat perfunctory or obligatory or sometimes hollow, and sometimes even a kind of indoctrinating experience, whether that indoctrination was focused on devotion to Israel, or around the gender binary.

So in some ways, the book is a resource for young people now who deserve honest responses and direct responses to their questions.

It's also for the rest of us who are still grappling with these questions, and grappling with how to have a relationship with Judaism that is beyond Zionism, and connected to the liberatory traditions in Judaism.

What is liberating here? What are the kinds of liberation people can seek through a ritual like this?

There's so much wisdom and creativity embedded in all of the traditions that we get through Judaism. The Bat Mitzvah gives people a year to study and grapple and learn, and then to speak back to their community. What a gorgeous tradition. What a beautiful, beautiful modality to offer young people just to listen and to engage. And I just love the value placed on study.

Many of our holidays and rituals have also been used and co-opted as tools of oppression and Zionism, and a kind of indoctrination.

But they've always been reclaimed. They've always been in that struggle between interpretations.

Using these rituals to not mask social problems, but to address social problems.

You’re producing a marathon reading of this book on Mother’s Day at St. Mark’s Church, in New York. Why is it meaningful to host this on Mother’s Day? And — also — how do you think about family and what family means when doing this work?

We are made possible by our movement elders. We are made possible by the grandmothers of our movement, who have, for decades – when it was much, much more lonely – held down a refusal to conflate Judaism with Zionism, and an insistence on solidarity with Palestinians.

One of the greatest blessings of my life has been to get to work so closely with so many of our Jewish women, our elders who are anti-Zionist and anti-racist. They have taught us how to live a life in the movement and how to live a life in the struggle.

They have taught us that it is not just what you believe, but also how you are with others.

So when I think about family, I think about political family and movement family.

Many of us long for relationships with elders who not only gave us our commitment to justice, and not only those who won't judge it or say, “Oh, you're just being childish and youthful,” but who will say, “Thank god you're being childish and youthful!” and “Thank god you're being committed to justice!”

Elders who are proud of the risks that young people are taking.

That's the best part of the sacred mending of the world.

It's not — as the media would characterize it — a generational rift.

It's an intergenerational legacy.

We want to be part of each other's liberation, not each other's oppression.

So it feels really fitting to have this event on Mother's Day, particularly given the radical history of Mother's Day, the anti-war history of Mother's Day.

The book is based around celebrating question-asking as really core to Jewishness. I think that doubt and faith go together in a certain way. How does question asking lead to action?

Gregg Bordowitz’s essay, which is the first in the book, responds to the question, “Why do Jews love questions?”

To him, our job as human beings is not to wait for divine intervention, but that we are here to intervene. That is our job.

To pursue justice, and to use the skills and resources and platforms and relationships that we have access to to make the world a better place.

Particularly when harm is being done in our name, it is our responsibility – our ethical, moral, and I would say spiritual responsibility – to be part of repairing and stopping that harm.

I think my greatest teacher in faith is our liberation movements, because they’re truly where we are taught to devote ourselves to a world we may not see in our lifetimes, but that we need to fight for as if it's possible in our lifetimes. And it should be.

What do you say to Jews who feel like they're losing something too big and too important if they start to disentangle their Judaism with their Zionism, or their support for Israel? Like, those who would say, “We cannot be safe.” What do you say to them?

One of the refrains that I keep going back to – for years now, and definitely over these past seven months – is that everything we want is on the other side of solidarity.

I truly believe this to the depths of my being: Everything we want -– we want safety, we want dignity, we want a sense of interconnectedness – we get that through solidarity.

We get that by saying “Whose house is on fire? What can I do to stop that fire?”

We have these false refuges that we've been offered. I think about false refuge all the time – about various forms of superiority that are offered as false refuge for things that we really want and deserve – things like safety and belonging and dignity and connection.

They don't actually get us those things. Militarization and militarism of any kind doesn't actually get us safety. Securitisation doesn't actually get us safety.

So this fallacy, this fantasy, this illusion that militarism, that racism, that borders, that walls, that ideologies of supremacy and superiority, can keep us safe or give us dignity: it's just not true.

We deserve so much more. We have a responsibility to ensure that what is taking care of us is not killing someone else. That is our first responsibility.

A number of these contributions are by Palestinians, Palestinian people who are older now and reflecting on their youth. What is it that you would want Jewish young people and older people to learn by hearing directly in this way from Palestinians in this context?

Unfortunately, because of Islamophobia, and anti-Palestinian racism, and anti-Arab racism, many of us as Jews, don't grow up hearing directly from Palestinians.

So it's very important that Palestinians are able to narrate their own experience and their own history.

It is very much under attack in this country, for Palestinians to be able to literally speak, and literally just be able to articulate the very basics of their identity, their history, their dreams, their experience.

So any B-mitzvah that is aiming to help Jews connect to the radical Jewish solidarity tradition requires that we listen to Palestinians directly.

We are very blessed to have so many wise and generous Palestinian teachers who are sharing with us about what their symbols of resistance mean to them, and about their own family histories, and about their own dreams for a liberated Palestine.

If this newsletter is meaningful to you, it would mean a lot to us if you would share it with someone who would enjoy it, using the link below. Your subscriptions, likes, comments, and shares make a big difference in making this newsletter sustainable. Thank you!

MATRIARCHY REPORT is written by Lane Anderson and Allison Lichter.

Lane Anderson is a writer, journalist, and Clinical Associate Professor at NYU who has won several journalism awards for her writing on inequality and family social issues. She has an MFA from Columbia University. She was raised in Utah and lives in New York City with her partner and young daughter.

Allison Lichter works at the Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York where she’s an associate dean. She has been a writer, producer and editor for radio and print, covering the arts, politics, and the workplace. She was born and raised in Queens, and lives in Brooklyn with her partner and daughter

Love this message for Mother’s Day. It’s reminding me of the Mother’s Day Proclamation written in 1870 calling for peace.